The conquest of luxury goods in Korea is largely based on the soft power promised by Hallyu. This wave of Korean cultural products is all the more seductive for brands as it knows how to capture and unite particularly committed communities of fans.

This is undoubtedly THE hidden reason behind this craze for luxury brands, which from Louis Vuitton to Loewe, not forgetting Chanel and Bvlgari, announce members of k-pop music groups among their brand ambassadors: to speak first to the digital community of these artists.

The system works first and foremost to appeal to Asian populations operating by mimicry, a springboard hitherto exploited by brands through their influencers or KOLs (Key Opinion Leaders).

The aim is also to appeal to Western populations (essentially American and European) attracted by the exoticism and fantasized vision of the country embodied by K-pop artists.

Having seen the fundamentally optimistic dimension of these productions, let’s move on to their community force.

A highly committed community

In Asia – and even more so in China and Korea – the notion of group remains central.

As co-author and sociologist Sophie Octobre explains, “In K-pop, these are groups that are always very much in love, that emphasize their sisterhood or brotherhood and that, instead of having a leader and followers, emphasize in a particularly assertive way the contributions of each individual to the whole. Contributions that are different, complementary and of equal value. ”

The power of the idol to prescribe purchasing behavior is also major. The idol acts as an influencer, except that his power is far greater than that of his counterparts in Europe with their fans.

Indeed, if there’s one thing that sets K-pop apart from other elements of pop culture, it’s the powerful emotional bond that binds idols to their fans.

For Thomas Sommer (SG Entertainment), the result is “an extremely close-knit family spirit with strong feelings of common belonging. A filial piety characteristic of a society marked by Confucian values since the 14th century, accentuated by the country’s island culture.”

What’s more, each K-pop group has a community of fans with whom it can interact on the various social networks via its own name: BTS have their A.R.M.Y. (short for “Adorable Representative M.C for Youth”, BlackPinks their BLINKS, a contraction of the group’s name, and Girl Generation their S♥NE (wish), an allusion to one of the group’s flagship tracks. By 2020, there were 750,000 fans in several hundred countries.

This ability to build up an army of admirers ready to do anything to defend their Idols is enough to make the biggest luxury brands jealous, as they seek engagement on Western social networks whose reach is constantly decreasing and budgets exploding.

As Thomas Sommer (SG Entertainment) explains, “Fans are getting organized to help their idols.” This support can be financial, or it can even lead to over-commitment to YouTube videos of their favorite band’s songs, to the point of skewing the results.

The CEO of the Korean entertainment agency adds “Currently BlackPink’s ddu_ddu.du remains the most viewed K-pop production on Youtube with over 2 billion views on Youtube. Apart from Gangnam Style – but that’s an exception – no group apart from BTS and BlackPink exceeds one billion views on YouTube.”

Transparency and personal development

K-pop’s other advantage in winning over Generation Z lies in its freedom to talk about mental health.

For sociologist Sophie Octobre, the Korean concept of JEONG is no stranger to this relationship. A concept that has no equivalent in French, but which could be defined as “a love of others that manifests itself in the smallest everyday attentions” – the opposite of the heroic love that permeates all Korean culture, including K-pop.

This generalized benevolence is reflected in messages from K-pop groups to their fans such as “take care of yourself” or “bundle up, it’s going to be cold”.

For co-authors and sociologists Sophie Octobre and Vincenzo Cicchelli, Korea cultivates a hemostatic system where “if something changes, everything must change to regain equilibrium.” This philosophy is a key element of the country’s social emotions.

If most cultural products – music and TV series in particular – are particularly inclusive in what they say, it’s above all because Korean society is not multiracial and is therefore very homogeneous, unlike China, which has 56 ethnic groups, even if the Han are dominant.

This predisposes them to speak to people who are homeless, disabled or simply unable to relate to others.

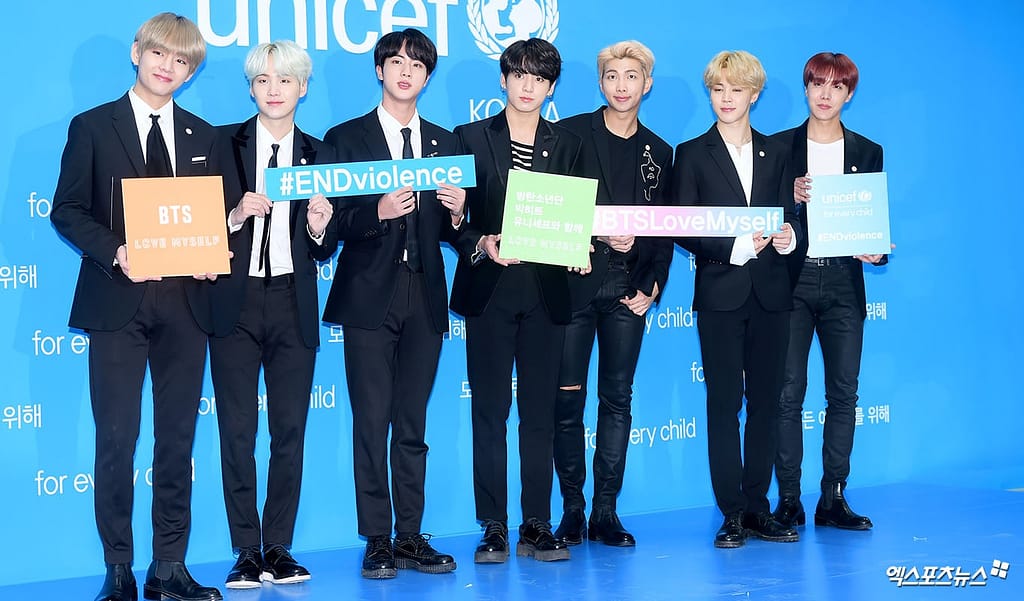

For example, the BTS group took part in the Love Yourself campaign, linked to UNICEF programs to support young people in their transition from education to employment by 2050.

The group has a whole discourse on “finding your way”, “talking about yourself”, “finding yourself”. Through their songs, they try to accompany people on this path, and that means dealing with harassment and psychological malaise without taboos.”

Thomas Sommer adds that one of BTS’s strengths is that they talk about the soul, a rather Judeo-Christian concept. In their album Map of the Soul, for example, there is an overt reference to the work of Carl Jung, the psychologist and disciple of Sigmund Freud.

So, like luxury goods, K-pop is often a matter of compensation, insofar as it helps young Westerners – mainly between the ages of 12 and 25 – in the midst of an existential crisis to find a purpose and a refuge from their anxieties or the loneliness of everyday life.

This typically Korean notion of JEONG is the added value of K-pop, according to Thomas Sommer at SG Entertainment, who incorporates this emotion into his agency’s work: “What we offer is content that emphasizes compassion. In this, we are in line with traditional Korean culture, which features very strong emotions.”

In the space of three generations, this society has gone from starving cohorts to globalized young people, in tune with the issues of degrowth, environmental protection and gender equality.

The result is extremely strong social pressure from the time they start school, with an extremely tense job market and one of the highest suicide rates among young people in the world.

In our fifth and final installment, we will take a look at the concrete expression of this win-win relationship between brands and artists: luxury sponsorship, notably through the testimony of K-pop production company SG Entertainment.

Read also > [INVESTIGATION] South Korea: When Western luxury courts K-pop (Part 3/5)

Featured photo : © Press